The line and the movement

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.15168/xy.v1i1.11Abstract

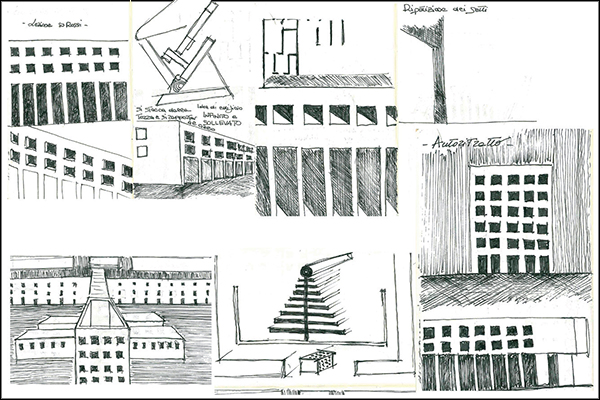

A line, in its most pure dimension, is a track imagined, it is a mental concept which captures and displays thoughts and things on paper. In Naturalis Historia, Plinio il Vecchio discusses the dispute between two painters, Apelle and Protogene, concerning the idea that, above all, a drawing is a line generated by the movement of the hand. This tracing movement is truly extraordinary because it represents the founding act of all figurative art: it isn’t a concept of material and mechanical action, but the mind’s expression of thought itself. In the Humanist tradition, the gesture of the hand becomes a symbolic act. In De Pictura, Leon Battista Alberti speaks of circumscriptione as an intellectual process of defining the image. Drawing is thus understood as the privileged forum for invention and as the foundation of the three figurative arts. Giorgio Vasari is aware of this when he speaks of drawing as the “father of our three arts”, as is Federico Zuccari in his distinguishing between disegno interno and disegno esterno. In this dimension, drawing is the mind’s expression of thought itself: it is born, takes form, and concludes on paper. Drawing has the extraordinary capacity to make things visible, to encourage a certain way of seeing these things. Viollet-le-Duc discusses this rudimentary question of “knowing how to see” in his Histoire d’un Dessinateur: seeing entails the critical and interpretative reflection of what the architect observes. In this vein, Paul Valéry sustained that “seeing in order to draw” involves overcoming one’s usual way of seeing. The line, which circumscribes each and every entity, therefore has a fundamental value for the architect because it is the element which allows the architect to decipher reality and conceptualize experimentation and creativity. Drawing, using the purity of the line, probes reality, penetrates into the depths of things and thought, spiraling onward, not enclosing entities but endlessly generating new ones.

References

BELARDI, P., 2012. Nulla dies sine linea: una lezione sul disegno conoscitivo, con una nota di A. Cantàfora. Melfi: Libria, pp. 100.

BRUSATIN, M., 2001. Storia delle linee. Torino: Giulio Einaudi, pp. 183.

DE RUBERTIS, R., 1998. Il disegno dell’architettura. Roma: Carrocci, pp. 260.

DI NAPOLI, G., 2004. Disegnare e conoscere. La mano, l’occhio, il segno, collana Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi. Torino: Giulio Einaudi, pp. 495.

FOCILLON, H., 2002. Vita delle forme, seguito da Elogio della mano, trad. it. di S. Bettini, prefazione di E. Castelnuovo, collana Arte. Architettura. Cinema. Musica. Torino: Giulio Einaudi, pp. 134.

KLEE, P., 2010. Diari 1898-1918, con una nota di F. Klee, trad. it. di A. Foelkel, prefazione di G. C. Argan. Milano: Il Saggiatore, pp. 426.

KLEE, P., 1984. Teoria della forma e della figurazione, ed. it. a cura di M. Spagnol e R. Sapper, prefazione di G. C. Argan. Milano: Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore, vol. I, pp. 534.

PIZZIGONI, A., 2001. L’aula di Minerva: 5 lezioni di disegno dell’architettura. Milano: Bovisa, Facoltà di Architettura Civile, pp. 96.

PURINI, F., 1996. Una lezione sul disegno, a cura di F. Cervellini e R. Partenope, con un saggio di G. Contessi. Roma: Gangemi, pp. 111.

PURINI, F., 2010. Un quadrato ideale. Disegnare idee immagini. 40, 2010, pp. 12-25.

SCOLARI, M., 1982. Considerazioni e aforismi sul disegno. «Rassegna». 9, 1982, pp. 79-83.

VALÈRY, P., 1996. Degas, danza, disegno. In Scritti sull’arte, trad. it. di V. Lamarque, postfazione di E. Pontiggia. Milano: Guanda, pp. 7-69.

VIOLLET-LE-DUC, E. E., 1992. Storia di un disegnatore. Come si impara a disegnare, introduzione di F. Bertan. Venezia: Cavallino, pp. 201.